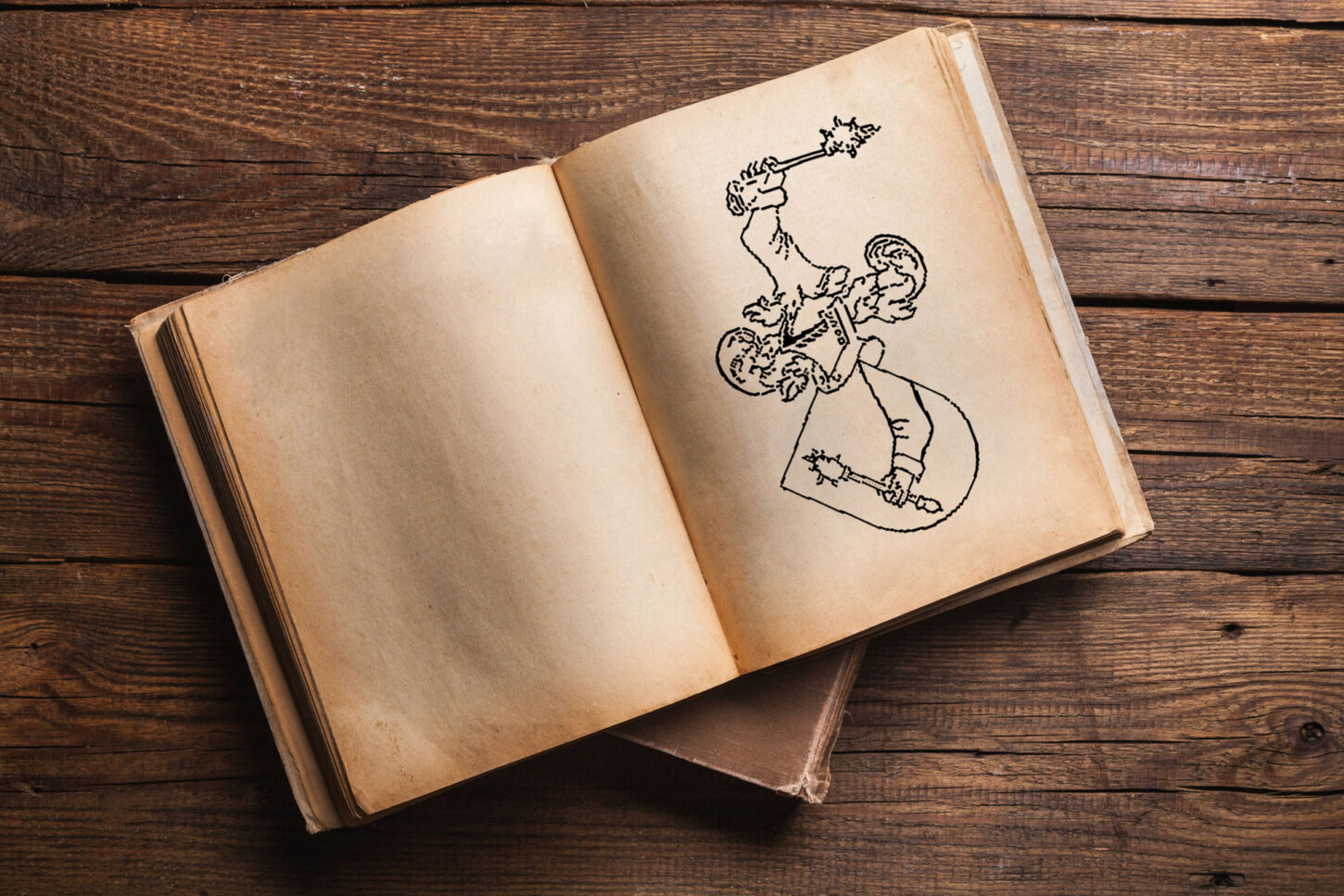

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of the family

On the development and interpretation of our family coat of arms.

Older form of the family coat of arms

- Shield: In blue a right arm, dressed in yellow, holding an iron morning star.

- Helmet ornament: Arm as in shield.

- Helmet cover: Yellow and blue.

Source: Coat of arms collection I by Benedict Meyer-Kraus (Staatsarchiv Basel, Wappenslg. A 18).

Younger form of the family coat of arms

- Shield: In blue a right arm armed with yellow (or gold), wielding a yellow (gold) or steel (or silver) mace, the hand clad with right yellow (or gold) glove.

- Helmet ornament: Arm as in shield.

- Helmet cover: Yellow (or gold) and blue.

Source: Coat of arms collection I by Benedict Meyer-Kraus (Staatsarchiv Basel, Wappenslg. A 18).

- 1560 Bartlin (§ 2): Seal, arm in sleeve with morning star.1584 Hans (§ 3 or 16): Family book Leonh. Binninger, arm in yellow sleeve with morning star in blue.

- 1596 Hans (§ 16): Pedigree Goetz, arm in yellow sleeve with white cob in blue.

- 1605 Jacob (§ 263): Arms target in shooting house, arm in yellow sleeve, butt stock and pommel yellow, butt head white.

- 1630 John (§ 294): Hieron coat of arms book. Vischer, sleeve with morning star.

- 1650 John (§ 17): 1674 renewed collective disk in Margarethenkirchlein, arm in yellow sleeve with white butt.

- 1652 Benedict (§ 8): Seal of the imperial notary, sleeve with cob (jewel: buffalo horns).

- 1656 John (§ 17): Collective disc in the forge guild, sleeve yellow, butt white.

- 1666 Martin (§ 32): Coat of arms book of the Household Guild, armored arm with flask, sleeve and flask yellow.

- 1667,1673 Martin (§ 32): Collective disk in the Margarethenkirchlein, yellow sleeve with white butt.

- 1686 Coat of arms book smiths, arm with morning star.

- 1695 Martin (§ 32): Coat of arms disc in the guild house to housemates, yellow armored arm with flask.

- 1918 Coat of arms book of the city of Basel by W. R. Stähelin (§ 232,1), sleeve with morning star.

When considering our coat of arms, the following main question arises: why does the bourgeois, shirted arm holding a primitive, spiky morning star become the armored arm of a knight holding an elaborately stylized mace?

a) If we start with the name, we find that stehelin, stähelin, stahelin is the Middle High German adjective to the noun stahel (= steel) and simply means steely, made of steel. The form stahelin, stehelin is still common in the 16th century, and we even encounter it in the 17th century. Because in Upper German the h thickened to ch, stähelin was pronounced like stächelin. Thus, even the Basel Johann Jakob Spreng, professor of German, in his Idioticon Rauracum (dictionary of the Alemannic language), completed around 1760, lists the adjective "stächelin" as "steely". The adjective stähelin is used not only in a direct sense, as a designation of the material from which something is made, but also in a figurative sense: it then means as much as hard, indomitable, particularly strong, resistant. For example, Sebastian Franck (1499 to 1542), who died in Basel, says: "The German Landsknechte seyen Teufel or aber stähelin." Another saying from the same period is: "If our bodies are not stähelin, they are not wehrhaft." It should be noted in passing that the adjective stähelin is also used in a legal sense; stähelin then means as much as "belonging to the iron stock". "Ain kuo die stählin sin soll" is not a cow with particularly hard meat, but a cow that belongs to the iron stock of a lease or sinecure and may not be sold1.

As a family name Stähelin or Stehelin is documented in various places since 12002. It indicates a characteristic of the bearer, either because he had special physical powers, or because he had a "steel" profession. The name research rejects a derivation of the name from the old Germanic with stahel compound call names as for example Stahalhart, since these names disappear after the 9th century and the name "Stähelin" appears only in the 13th century, thus after a gap of four hundred years. It is rather an epithet that was given to the blacksmiths in any case. So if for example a "Henricus dictus stehelin" is called, it means: Actually the man is not called so, but his environment uses to call him so3.

Something quite different from the word stahel, "steel," however, is the word "spike," which is used to describe anything that is pointy, such as pointed implements. Stachel is a new word and etymologically has nothing to do with steel. The word "sting" has been in general use only since the beginning of the 16th century; it goes back to stechen, Middle High German steken. At first it was used only in Middle and Low German, then under the influence of Luther's Bible translation also in Upper German. In the Basel Bible glossary of 1523, Stachel has yet to be explained: Stachel = iron point on the bar. Wider den Stachel lecken = to turn against the spike4.

b) And now to our coat of arms. Certainly, the morning star and the mace have the same origin in a relatively primitive club-like weapon, which may have been used mainly by peasants, but which was also common among the cavalry of the 14th century. As a peasant weapon, the morning star retained its primitive form in the Middle Ages. It was so unwieldy that it always had to be handled with both hands; in this respect, the depiction on our coat of arms is unreal. Such a wooden club studded with nails could be made by any peasant; later it was also forged from iron by a peasant blacksmith. It should be noted that, contrary to a widespread misconception, the morning star is not an ancient Swiss weapon. In the Swiss pictorial chronicles it is never seen in the hands of the Confederate warriors, occasionally only in those of the enemy. The old Confederates were much more effectively equipped with long spear, half-bar, sword etc. In Switzerland, the morning star was used by the insurgents only in the peasant wars of the 17th century; it was ineffective against well-equipped outriders.

From a primitive mace of the cavalry developed the mace. It was a knight's weapon, consisting of a handle with a ring or loop for hanging on the saddle, a short round handle, originally made of wood, later of iron, and then the actual butt part. This was originally spherical or flail-shaped; later it was also divided (as seen on our coat of arms) into radial strikers, which often had serrations or reinforced knobs at their ends. This made the weapon lighter and yet increased its effectiveness. In this form, the butt was called a "cuirass butt". It was not a main weapon, but only a supplementary one, its purpose was to be able to crush the bones under the plate armor by blows. It was only used when fighting in steel armor. In the Middle Ages, this butt was often combined with the adjective "stehelin", for example in Wolfram von Eschenbach's Willehalm: "Die truogen kolben stehelin" (395, 24); "mit den stehelinen Kolben" (396, 13). In the second half of the 16th century and in the 17th century, the mace became the badge of the mounted officer, and, in decorated form, the scepter of rulers and courts. As such, it persisted well into the 18th century5.

c) The first Stähelin who used the coat of arms with the morning star was Bartholomäus (§ 2), eldest son of the progenitor. Why did he choose this coat of arms? Should the hand holding the morning star symbolize the "steely" strength? Or did he feel the morning star as a typical "steely" weapon? Then he would have rather chosen a sword or the heraldically more appealing flask. It is more likely that Bartholomäus St. mistakenly took the name Stähelin, pronounced Stächelin, from the word Stachel, which was spreading at that time, and thus chose a very prickly object for the coat of arms: a typical example of the so-called speaking coats of arms. The first Stähelin who put the mace instead of the morning star, but still held by a behemde arm, in the coat of arms was, according to the findings of Professor Felix Stähelin, Hans Stähelin-Beckel (§ 16,1555 to 1615), namely in his entry in the family book (student album) of Jacob Götz in 1596 (Historical Museum). He was a seasoning merchant and master of the guild of saffron. He probably found the morning star too peasant and chose instead the more distinguished variety, the flask.

In the 17th century, the mace already appears frequently in the family coat of arms, but next to it still holds the morning star. Both were always rendered in white and silver color respectively, which corresponds to the correct derivation of the name from the word steel. The first person to use the armored arm with mace was head guild master Martin Stähelin (§ 32), in 1666 in the coat of arms book of the Hausgenossenzunft, on the occasion of his election as sixth (superior). Why did Martin Stähelin also replace the "bourgeois" arm by an armored arm? More likely than etymological considerations are external models that led him or the draftsman of the coat of arms to finally adopt the mace and armored arm into the coat of arms. A widespread coat of arms book at that time was the one by Johann Sibmacher, which was published several times in Nuremberg. There you can find coats of arms with the armored arm6 as well as those with the mace7.

In the years 1623 to 1631, the "Thesaurus philopoliticus" by Daniel Meißner was published, a book with a lot of city views, which, however, only served as background for emblems and moral slogans. On the view of the city of Stein am Rhein, an armored arm with a mace breaks out of the clouds in the upper right corner, in exactly the same way as Martin Stähelin had it drawn. He or the draftsman may have known Meißner's work and drawn inspiration from it.

Another reason for the change of the coat of arms could be heraldic considerations and rules. The coat of arms was originally a knightly sign (marking the unrecognizable in the armor); also the helmet above the coat of arms points to the knightly origin. To the knightly tournament helmet, as it was used in heraldry since the 16th century, the bourgeois arm with the morning star did not fit well. The stylistic unity was much better preserved when the knightly armored arm with the noble mace appeared under the knightly tournament helmet.

Moreover, an important heraldic rule states that in a coat of arms, color may never be placed on color or metal on metal, but only metal on color or color on metal8. A yellow shirted sleeve on a blue ground, as it can be found for example still in the Basler Wappenbuch, is, strictly speaking, heraldically inadmissible. Yellow is not one of the original heraldic colors anyway. On the other hand, gold is permissible as a metallic color. But since a shirt cannot be made of metal, it was obvious to change the shirted arm into an armored arm and thus create the heraldically correct "metal on color".

Finally, the following explanation could also be valid: In the 17th century, the importance and prestige of the nobility increased enormously everywhere. Political and economic developments, which cannot be discussed further here, led to a decline in the importance of the bourgeoisie and craftsmen in the imperial cities. After the Thirty Years' War, the age of princely absolutism began, in which, following the example of France, centralized administration and a standing army became the cornerstones of the state. The nobility dominated the administration and the army. The new educational ideal was the "cavalier," the "honnête homme," who had to know French, horseback riding and fencing. Instead of universities, academies of chivalry were founded, outstanding commoners were ennobled (Leibniz, Pufendorf). This spirit of the age has undoubtedly found its expression also in the coat of arms system9.

The Basel upper class of the 17th century did not give itself an emphatically bourgeois-democratic air, but behaved in an absolutist manner and, as the urban revolution of 1691 shows, attempted to form a new patriciate. The patrician, however, is noble according to ancient law. In Martin Stähelin perhaps the consciousness of belonging to a new upper class was alive. Therefore the effort for noble transformation of the coat of arms.

d) Which coat of arms is now the more correct one? Felix Stähelin believed that the sleeve with the morning star would correspond better to the humble beginnings of the family than the armored arm with mace. Conversely, the writer would like to give preference to the latter form for etymological and heraldic reasons. For the arm clad in steel armor, albeit gilded, holds a steel mace. The morning star, on the other hand, was generally not made of steel, but mostly of wood with nails, at most of wrought iron. It also reminds too conspicuously of the word spike, which, as noted above, has nothing to do with our name.

Andreas Staehelin-Wackernagel

1 Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch s. v. Stahl und stählen. - Swiss Idiotikon. Wörterbuch der schweizerdeutschen Sprache s. v. Sta(c)hel. - G. A. Seiler, Die Basler Mundart, Basel 1879, p. 276.

2 Urkundenbuch der Stadt Straßburg I (1879), p. 115ff. - Adolf Socin, Mittelhochdeutsches Namenbuch nach oberrheinischen

Sources (1903), p. 166f.

3 Alfred Götze, Alemannic name riddles. In: Festschrift Friedrich Kluge, Tübingen 1926, p. 51 ff. - Adolf Bach, Deutsche Namenkunde. Volume l, 1, Heidelberg 1952, p. 245.

4 Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch s. v. Stachel.

5 Wendelin Boeheim, Handbuch der Waffenkunde, Leipzig 1890, p. 357ff. - E. A. Geßler, Schweiz. Landesmuseum. Guide to the Weapons Collection. Zurich/Aarau 1928, p. 37 ff. Viktor Poschenburg, Die Schutz- und Trutzwaffen des Mittelalters, Vienna 1936, p. 137.

6 Edition of 1605, p. 29 Oppersdorf, p. 69 von Mestich, p. 75 Pelcken.

7 P. 35 von Kirchperg, p. 66 Kitschker, p. 144 von Ebeleben, p. 149 von Kappel.

8 See Eduard Freiherr von Sacken, Katechismus der Heraldik, Leipzig 1872, p. 13, - Bert Herzog, Wappenschild und Helmzier, Bern/Leipzig 1937, p. 10.

9 As an example similar to ours, the Favre (Schmid) family from Valais is mentioned, in whose coat of arms a bourgeois

arm, which beats with a hammer on an anvil, also changed to a knight's arm, and where the anvil was replaced by a lion (p. 9).

anvil was replaced by a lion (Walliser Wappenbuch, Zurich 1946, p. 93). - Almost the same coat of arms as ours is used by the Vaudois

Ballif family (Armorial vaudois, Tome 1, Baugy 1934, p. 26).